By Gail O’Neill– October 8, 2019

Shortly after Gregor Turk earned a graduate degree from Boston University (M.F.A., 1989), he got a piece of advice that resonated: “If you don’t get a studio right away, you have a good chance of not being an artist.” So he decided to put down roots on his family farm in Homer, Georgia, where he could manage the land with his brother, care for their ailing grandfather (who wanted to die where he was born and raised) and establish his daily practice as a sculptor.

To this day, Turk refers to himself as a topophiliac for sharing his grandfather’s deep affection for place. His affinity for geographic region and cultural identity, however, has no boundaries.

The Atlanta native is inspired by atlases, markers and signage. His preferred materials are clay and rubber, the layering of which reference topography with their convoluted lines, turbulent currents and shifting elevations. He’s known for public art installations, ceramic sculpture, photography and mixed-media constructions that incorporate mapping imagery and cultural markings. His obsession with how arbitrary lines drawn on a map — with no consideration for native populations, culture or history — can alter landscapes and change lives is the focus of his latest one-man show, Reclaim/Proclaim Blandtown, at Gallery 72 downtown (through November 27). There’s an opening reception at 6–9 p.m. October 10 and artist talks at noon October 16 and at 7 p.m. October 24.

Part history lesson, part manifesto and part civic rousing, the exhibition explores the gentrification of Blandtown, which dates to 1872. The neighborhood in northwest Atlanta was founded by Felix Bland, an African American man. It burned in 1938, was redlined in 1931, rezoned in 1956, razed in 2008 and rechristened West Town by developers in 2016. Turk is determined to set the record straight.

“My incentive has been to raise awareness about gentrification and the undertones related to class, race and intentional disruption of a neighborhood,” he says. “There were 21 houses in Blandtown — originally 300 or 400 homes — when I bought my place in 2003, but only four of those original structures remain.”

Once home to four churches, a public health clinic and a dime store, the neighborhood was in steep decline when Turk bought his single-story cinder-block house there for $85,000. The place was built by Johnny Lee Green for his family of seven in the late 1940s and was an artist’s dream for its affordability, manageable size and long-term suitability. Casual conversations with Green and son Wallace inspired Turk to collect more oral histories from other longtime residents. Doing so inspired his resolve to safeguard the happy memories of a once vibrant, close-knit community on the brink of extinction.

In the interim, a Top Golf facility, a Bad Axe Throwing club and 45 single-family homes selling for $550,000 (with 75 more units to come) have sprung up around Turk’s humble studio. His place is known as a “nail house” for its owner’s refusal to sell to developers. A Southerner to the core, Turk welcomes new neighbors with vegetables from his backyard garden. The five-foot-high sign on his front lawn proclaims “Welcome to the heart of Blandtown” and has become a local attraction.

Turk laughs when he talks about the daily drive-bys and selfie-taking pedestrians attracted to his sign, and says the message is neither a commentary on the new architecture nor a passive-aggressive middle finger to developers. But he turns dead serious when discussing Georgia Tech Professor Emeritus Larry Keating’s book on Blandtown — Atlanta: Race, Class and Urban Expansion — as a case study for eliminating black clusters.

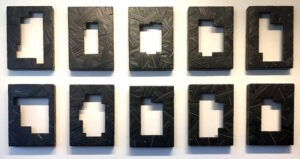

Turk considers the cultural bulldozing of gentrification a form of aggression. And as Blandtown’s ad hoc, one-man chamber of commerce, he wants to explore the shadow side of displacement through a combination of sculptural installations, agitprop posters, archival newspaper articles, photographs and a timeline of Blandtown. If Reclaim/Proclaim Blandtown provokes thought, inspires conversations and gets visitors to reconsider the scale and climate of the viable communities that preceded them, Turk’s work for the past three years will not have gone to waste.

“Gregor has always been at the cutting edge of social-justice art that did not sacrifice fine-art sensibility,” says Kevin Sipp, Gallery 72’s cultural affairs and public art coordinator.

“He discovered the history of a space where marginalized people settled before putting their family/cultural brand on the space,” Sipp says. “Suddenly, what was Blandtown is now West Town — a nondescript, non-cultural space that lost its historical character and narrative to development. Gregor’s exhibition is a reminder to people to reclaim, proclaim and never lose the narrative of this history because our awareness of those histories really defines who we are as a people.”

Original article on Arts ATL