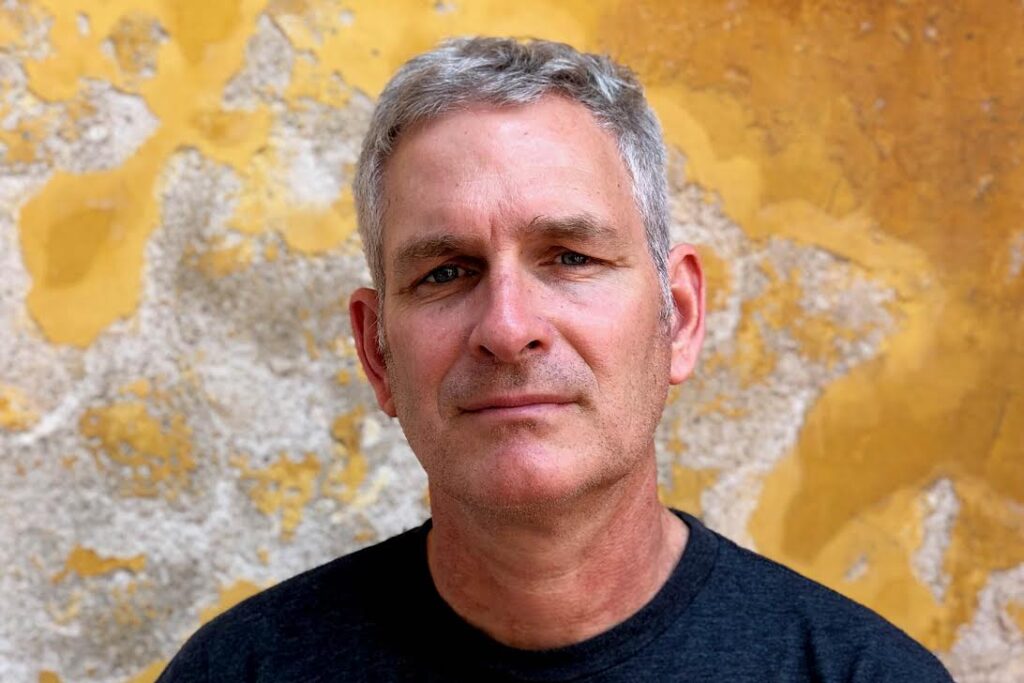

Shelley Danzy – April 7, 2021

“I’m a landscape kind of guy,” says visual artist Gregor Turk. “The great thing about public art? It becomes something else.”

It won’t take long to see what he’s talking about.

Both personable and humble, Turk is an artistic Renaissance man. From photography and design to ceramics, rubber and rubbings, he’s fascinated with geography, maps and signs, and tends to find distinctive ways to represent the kind of history that often gets bulldozed.

Blandtown Banners, his latest outdoor exhibition, features 25 red, white and black agitprop banners along the Atlanta Watershed Reservoir fence at Howell Mill and Huff roads in Atlanta’s Blandtown neighborhood (through April 28). He says he hopes that the banners prompt passersby, especially those stuck in traffic, to consider the town’s “history, rapid development and future.”

Blandtown was a prospering African American community for more than 80 years, until industrial rezoning took over. The banner photographs — each accompanied by a word with the prefix re — feature Blandtown landmarks (former and remaining), infrastructure and newly constructed projects.

Turk, 60, is a native Atlantan. He attended Sarah Smith Elementary near where Phipps Plaza stands today. He spent several years in Homer, Georgia, and did his undergraduate work in Memphis, Tennessee, studying psychology and religion, while taking just as many art classes. He spent two years in Liberia with the Peace Corps, then art won his heart. He earned an M.F.A. in ceramics from Boston University (1989). And although Atlanta-based, he continues to travel for many a residency.

His studio has been in Blandtown since 2003 and — like many Atlantans are — he’s not entirely comfortable on the highly developed Westside. While creating — often with Otto, his Portuguese Water Dog by his side — he thinks about ways to marry messages about Blandtown history with imagery and cultural markings.

Turk’s art is a life lesson. Always bold, sometimes obscure. On the Atlanta BeltLine in the mid-2000s his temporary installation Apparitions, featured five billboard images of Union Gen. William T. Sherman’s eyes. His illuminated sculpture Portal, which stands outside the Metropolitan Branch Library, features 25 repurposed stained-glass windows from a church that once stood there. Inside, his Passage features the shapes of more than 160 neighborhood buildings.

If you’re at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (Gates E33–36), you’ll see Turk’s Latitudes + Legends, a permanent 86-foot-long installation made of ceramic tile.

Turk spoke with ArtsATL about public art, plaques and postcards, and the messages in his humor.

ArtsATL: What have you discovered since living in Blandtown?

Gregor Turk: I took at face value that Blandtown was named after Felix Bland, who’d been given the land by Viney Bland, his White slave owner. About the same time my billboard went up, Dr. Rhana Gittens was doing research for her dissertation, which included Blandtown. Census records confirm that Viney wasn’t the slave owner’s name, but Felix’s mother, the Black wife of Samuel Bland. Check out our conversation, there’s so much to tell.

ArtsATL: Why the banners?

Turk: In the mid-1950s, Blandtown was rezoned from residential to heavy industrial. When I bought here in 2003, there were 21 of the 200-300 original homes. Only a few former residents were living here. There were shelled-out buildings and the writing was on the wall. The developer was buying up everything. They kept knocking on my door and I had no interest. By 2016, this whole new neighborhood was built, then rebranded West Town by Brock Built. I made a “Welcome to the Heart of Blandtown” billboard and placed it in my front yard, showing an Indian-head test pattern used for calibration when black-and-white TVs went off at night and came back on in the mornings from the 1940s to the 1970s. That billboard and these banners are a statement that the whole neighborhood is gone and a new neighborhood is tuning out what’s going on.

ArtsATL: What’s the significance of hanging the banners on the watershed fence?

Turk: It’s where the traffic backs up! Maybe the banners don’t do anything for you the first time, but the second or third time, the words start to play images in your head. It appears as propaganda promoting the neighborhood, which it does, but it’s also pretty honest and looks at it in terms of development. Positives, negatives and then also these sort of coded histories. Hopefully, it’s just enough to motivate curiosity for people to start talking about it. A number of people have gone on the internet and started doing some research, which is really what I’m after.

There are 25 banners right now, four with the original art that I did for my show Reclaim/Proclaim Blandtown in 2019. The way I arranged the banners is that coming from Huff Road there’s only one banner about half a mile before the rest of them. You see it and it doesn’t many any sense. You see the same thing done in the same way coming off Howell Mill Road. Then you get this concentration of the 23 of them together. And it tells you what’s going on. It was meant to kind of bookend an image of what you didn’t notice and now, what you just saw.

ArtsATL: Why the affinity for public art?

Turk: My work deals with mapping, geography, cartography, so place is paramount. I guess it’s a pet peeve of mine to see a call for a project or public art pieces, you know to create a sense of place. To me, that’s such an artifice. You reinforce a sense of place, not create it. It’s a matter of discovery and telling the correct story. That’s what comes to me. For Blandtown Banners, the story we’ve been given for decades, the narrative, the origin story is not correct. Even though I’m the White guy helping to tell the story, I think it’s kind of a universal story.

ArtsATL: Why the prefix “re”?

Turk: I do enjoy wordplay, and I think it works best when the prefix word is different than the meaning of the word. For example, “redoubt and doubt” have two very different meanings, as well as “retrench and trench,” “retell and tell.” It’s built up over generations of a historical site. I find those moments the most successful rather than something like “source and resource.” They’re not that different. Just like sitting in traffic. If you’re like me, my mind goes in different directions. I still learn something from the words since there are different ways to interpret them.

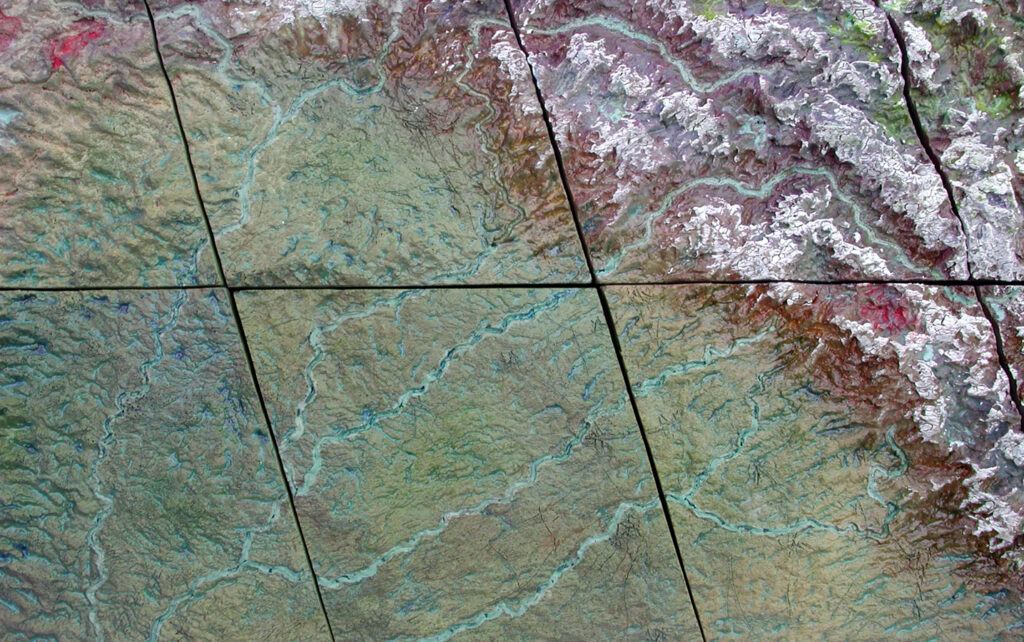

ArtsATL: What sparked your interest in maps?

Turk: Definitely geography. I do recall around 4 years of age I would come in and dump the shapes of the wood cutouts of the U.S. map onto the floor. I would close my eyes and feel the shapes with my fingers. It must’ve been an odd sight to see this kid day after day doing this, but I memorized it. Mapping has been about the physical elements, which comes through in my work. It’s more about the concept of mapping. I think it’s really fascinating in terms of just how you ask somebody to give directions, because your landmarks aren’t the same as my landmarks.

You know those free maps we used to get at gas stations? As a teenager, I was riding my bike and there was a street called “Tellalie.” It didn’t exist. I kept going around the block because it was supposed to connect two roads. Years later I realized that it was a Rand McNally and other mapmakers’ technique to put in false information in an insignificant place so they’d know if their maps had been copied. I realized that that street was “tell a lie.” Maps are about our relationship with our environment. With digital mapping, we’re not even looking at the landscape. We’re looking at cues from a device, but it’s interesting how we route ourselves now.

ArtsATL: How does mapping affect your identity as an artist?

Turk: Abstract lines actually have meaning. When I was doing research for my thesis, I started thinking about the longest, straight border in the world, which is the 49th parallel at the border between Canada and the United States. It runs 1,270 miles. It’s clear-cut. It’s like a power line clearing with no power line. I traveled by foot and bike and made a documentary on how this line affects us. The simplest way to describe myself is “I’m a Georgian defined by the 35th parallel (Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia border). I’m a Southerner, defined by the Mason-Dixon line, and American, defined by the 49th parallel.”

ArtsATL: What do you collect?

Turk: Car plaques! I find American car names fascinating. They change every decade. Since the 2000s, it’s been more science-related names like Ion, Matrix, Caliber. The ’80s had names like Regal. Then there’s the whole western theme of cars. I have more than 200 physical car plaque names that I’ve arranged thematically. I make rubbings right off them. I also collect postcards. I came across a stash of them at my grandfather’s house. I laid them out and started making connections to the image of a place and how that’s portrayed. There’s a lot going on in a postcard. Back at the turn of the century, you’d see a flag that was always fluttering. Then there’s the text that goes with the image, which is important to the time period. You start to look at imagery in terms of typologies, like the curve of a road like a curve in the road seems to be a very redundant image. What’s there is not apparent right away. What’s the greater meaning? The text on the back of a postcard can be agenda-driven. I would always underline words when I sent postcards, pointing out some of the ridiculous adjectives used.

ArtsATL: How do you use humor to make a statement?

Turk: On April Fools’ Day, I designed a virtual mock-up of a Blandtown Banner that said “East Blandtown” on the façade of the High Museum and posted it to my Instagram. It was my statement about how Blandtown had been called West Midtown. Why not flip that over and think of Midtown as East Blandtown? Early that morning no one had spoiled it yet. Folks played along . . . or were fooled.