Lauren Highsmith, Emory University – November 14, 2019

Recently Atlanta Studies sat down with notable contemporary visual artist Gregor Turk to discuss his current Gallery 72 exhibition, Reclaim /Proclaim Blandtown, as well as his relationship to the gentrifying neighborhood just northwest of Midtown. His exhibit combines sculptural installations, works on paper, and photographs to explore the history and transformation of Blandtown. The gallery is physically divided into two parts, which also signify Turk’s two objectives for this exhibit and his larger ongoing project about the area: Reclaim (the history of Blandtown) and Proclaim (as a reconsideration of the neighborhood’s derided name). This exhibit has also notably been supported by both an Idea Capital Grant and an Artist’s Project Grant from the Mayor’s Office of Cultural Affairs. See the exhibit for yourself at Gallery 72 in downtown Atlanta, where it will be on display through Wednesday, November 27. Gallery 72 is open Monday–Friday, 10am–5pm.

We recognize that Turk and his exhibit provide only one perspective on this neighborhood and its history and we hope to publish more of the many perspectives on this neighborhood in the future.

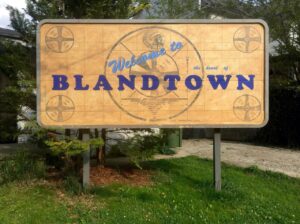

Thank you for the invitation to visit your studio. It was quite a surprise to realize that your studio was actually a house – and a smaller, much older house at that. In the midst of a redeveloped neighborhood is this studio that – according to the billboard in the front yard – marks “the heart of Blandtown.” Let’s begin by discussing the installation of that billboard.

My intent with the billboard came in 2016 when the development of this whole neighborhood was just about being finished. I know that the developer Steve Brock of Brock Built was branding this area as West Town – again, anything but Blandtown. People were coming in and asking about West Town, and I said, “West Town? This isn’t West Town. This is Blandtown.” So I put up the sign. The sign was also a statement about what has happened. I used the Indian Head Test Signal, which was big in the ‘30s, ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s, through the ‘70s on television. When television went off the air at the end of program for the day, that signal went up. I was making a statement saying the old neighborhood is off the air. Now this new neighborhood is coming. What’s it gonna be? And then I put a patina of dirt from when the house next door was excavated, I saved some of the dirt and I stabilized it. That’s what makes that orange, that kind of ochre color. It’s somewhat nuanced, but very intentional. At the top of the billboard, you’ll see the Indian Head. I replaced the grid with Felix Bland’s name. Then I did this sort of almost cheesy “See Rock City” kind of thing and strategically placed “Welcome to the heart of Blandtown.” It’s been almost three years now since the installation [of the billboard]. It’s holding up pretty well.

Has there been any significant response to the billboard?

In 2017, Rhana Gittens, a Communications PhD Candidate at Georgia State University, was doing a photoshoot at The Goat Farm. She was struck by the name Blandtown, got curious about it, and started doing research. She also saw my billboard claiming that the name is Blandtown; so she did primary research, and we’ve been sharing information and contacts. The given narrative has always been that, after the Civil War, Viney Bland was the white wife of a slave owner. She gave freed slave Felix Bland (same common name) a Tuskegee Institution education and several acres of land. He lost the property for not paying taxes. Rhana got census records, land deeds, things like that with actual names. And the great thing about the census records is it has the race of the person on there. Well, Rhana found out that Viney Bland was Black and was married to Samuel Bland, who was also Black. I don’t know if Samuel and Viney were freed or were already free men prior to the end of the war. Regardless, just a few years into Reconstruction, she found documentation that they had deposited $200 at the Freeman’s Bank. That then became the purchase of four acres of land in 1872. Felix was one of their children; and that’s how he got the land. So that narrative of the benevolent slave owner is totally gone now. I think Rhana’s discovery gives deeper understanding of the neighborhood that did not exist before.

Read more about Rhana Gitten’s research into Blandtown’s origins here.

You had been working here in this studio for some time before installing the billboard, and clearly before the recent wave of development in the neighborhood. How did you first come to this place?

After my studio tenure at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center ended in 2003, I wanted to buy a place so I would not have to move my studio again. I settled on nearby Blandtown for its affordable price, relative proximity, and zoning (light industrial). The block I bought a house on was truly mixed-use: there were three households, a cabinet-making shop, a wood-workers studio, a crack house, and two dilapidated houses occupied by homeless men.

Alongside the propaganda-like pieces from the “Red, White, and Black series,” photographs that show the history or re-envisioned history of the neighborhood, and the more self-evident works, your current exhibit includes a number of more abstract pieces. Could you explain how those pieces connect to your aim to encourage a deeper understanding of Blandtown?

I have made twenty boxes that represent the footprints of the old houses in the neighborhood. I found out I have to make another one because I discovered just in the last few months that one of the churches going up Huff Road was a house that was converted into a church. That makes twenty-one houses that were here when I moved here. I want to pay tribute and recognize the houses here when I got here.

Besides the name, is there more that you want people to learn, proclaim, or reclaim about Blandtown from your exhibit?

I think there’s power in knowing the history. Blandtown is a name that you can have fun with without knowing anything about the history. But I think the deeper meaning is that people would take ownership of that name if they knew the rich history. The weird thing is, there’s nobody here of original residence. There was a diaspora of sorts that took place in the seventies. Things became so bad here, and part of that was because of the zoning process. You couldn’t make improvements to your house worth over fifty percent of its value. So think about the value of these houses, which is next to nothing to begin with. Anything you did was going to be more than fifty percent of the value. That led to this precipitous decline, and, by the seventies, people wanted out. I mean, there were better opportunities, even by the seventies, of course. I believe the majority of the former residents moved to the Cascade area.

It’s been interesting talking to both Mr. Green – Johnny Lee Green – the man who built and originally owned this house, and his son Warren. They had sort of different perceptions of moving away from here. One of the older, more supposed Jim Crow mentalities was, “Oh, yeah, it’s time to go,” which caused those original residents to move. I think Warren felt more that they were forced out. Warren also references that this was a tight community. It may have been poor, and there may have been a lot of unappealing aspects about it, but it was a true community. I think that’s true of a lot of hard-hit communities, you know? You’re all in it together. But these are the different perceptions on the breakdown of the community.

So how did you get that ownership back? Everybody’s gone, with the exception of one of the churches that does have former roots here. So, you know, I find myself in a position, especially being a white person, asking, “What place do I have in telling this story?” You know? I think home is important to everybody. And the loss of home, I think that that is universal – regardless of one’s race.

How do you understand your position in the neighborhood? And what are your thoughts on being the artist to provide a voice for it?

I feel like I’ve landed in the right place, with a place in transition that nobody wants to claim, and all the people that were passionate about it having been displaced. Before rezoning, the African American community was able to thrive here despite all the odds against it. But by the fifties, Blandtown was perceived as more desirable for industry. In his book Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion, Larry Keating actually uses Blandtown as a case study of eliminating black residential clusters through rezoning.

In a way, I’ve realized I’m an unofficial artist-in-residence. Because, if not me, who’s going to do it? And I don’t mean that in an arrogant way at all. I think so much of it is getting the story out. The ownership is secondary. I see myself as the bridge between the old residents – the former residents – and the current residents. I feel strongly that losing the history of Blandtown is a real loss. I mean, I don’t understand moving into a place and thinking that it’s neutral territory, that it has no history. Nobody now is responsible for what happened, but we still have to account for it and recognize it.

I think the name can be, will be claimed again. But there’s still a lot more to do, you know? And I do hope that others get involved. We should look into the histories of those displaced residents if we really want to uncover the story of Blandtown. It requires somebody going deeper. And now is the time to do that. Mr. Wallace Bibbs, the man who bought the house from Mr. Green and sold it to me, is 80 years old . . . The clock is ticking for all of these people with the knowledge who are dying.

We believe Reclaim /Proclaim Blandtown provides an opportunity for more than passive consumption; it is a provocation for the public to seriously consider the importance of collecting oral histories and preserving cultural archives, uncovering and rediscovering our own histories, and taking pride in the place(s) we call home. And Turk’s take on these issues is far from the only one. We are interested in featuring the wide array of perspectives on gentrification and displacement in Blandtown and other neighborhoods like it throughout our city, so we encourage all to submit their own reflections on these issues and join the conversation on the critical issue. You can find our guidelines for submission here.

Original article on Atlanta Studies.